Albert Einstein is quoted as saying, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” Thomas Edison, on the other hand, said, “Genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration.” Both of these men are remarkably creative, but their angle of vision is obviously worlds apart. So how can both of these statements be right? This is the subject I would like to address today.

First of all, I would like to dispel two myths about creativity. The first myth is the idea that creativity is a quality you either have or do not have. When I taught my college course on creativity, one of the first questions that I asked my students was how many of them thought they were uncreative. Usually, about 50-60% of them raised their hand. But then I asked how many of them played in the sandbox or with a dollhouse or lived in a fantasy world of make-believe when they were small children. Everyone raised their hand. Research has shown that at the age of 5, we are using about 80% of our creative potential. But by the age of 12, our creative output declines to about 2% and generally stays there for the rest of our lives.

So what happened on our way to paradise? For most of us, school became a part of our life with its rules and regulations and emphasis on the right answer and tests. Also, our parents and other adults began to tell us to grow up and stop daydreaming. Even our early Christian upbringing with its emphasis on right behavior and obedience to rules can have a smothering effect on the creative spirit. Admittedly, this is a sweeping statement and there are always exceptions, but I think most people would agree that these can be effective creativity killers.

So we see that we are all born creative. After all, we are made in God’s image, and the first thing God tells us about Himself is that He is creative. But another reason for the myth that creativity is something you either have or don’t have is the common idea that creativity is a noun, which implies that it is something tangible, capable of being possessed. But creativity is a verb, a process, something that you DO, not something that you own.

The second myth is that only extremely intelligent people are creative. This is quickly dispelled when we recognize that those who score high on intelligence tests usually score low in creativity. This is due to something that the creativity guru Edward DeBono calls the ‘intelligence trap.’ The short version of this is that highly intelligent people feel they do not need to learn anything more about thinking. But intelligence and thinking are not the same things.

He gives us an analogy of an automobile. One’s innate intelligence (I.Q.) is similar to the power of the engine. Thinking, on the other hand, is equivalent to the skill of a driver. He goes on to say that a highly intelligent person will often take a view on a subject and then will use their intelligence to support that view. The more a thinker is able to support a point of view, the less inclined he or she is to explore the subject. Failure to explore a subject is bad thinking! Add to this the fact that highly intelligent people don’t like being wrong or admitting an error because their identity is wrapped up in their intelligence, and you have that person trapped into one point of view by their ability to defend that view.

Three Axioms of Creativity

An axiom is a self-evident truth that needs no proof to verify. As a starting point for all creative thought, it would be good to start here. There are 3 parts to this.

1. Many Before One

This is also called divergent thinking. As an example of this, I would like to use the working habits of the author James Michener. For my younger audience, Mitchener was a best-selling, award-winning author from the mid-20th century who was very popular in his day. He allowed himself 3 years to write a book. Knowing that 3 years of his life would be consumed on this one project, he wanted to make sure it was the ‘right’ one. So he began by writing 10 one-page outlines on 10 different possible books. Then he put them away and took a long break. When he came back a week later, he looked over the 10 possibilities and discovered that during that time, 5 of the outlines didn’t look as good as they did before, so he eliminated those five.

2. Time is Our Friend

He then repeated this again for another week, and when he returned, he noticed that 3 more of the outlines didn’t make the cut. He scrapped them also. Then he took his last break. A week later, with only 2 outlines left, he realized that only one of them really stood out, so he eliminated the other one and now had his subject for the next three years. This is called convergent thinking, where you ‘converge’ on a problem. So what happened during those weeks of absence? Getting away from an idea gives us time to gain an objective point of view. Have you ever written a poem or made a picture that you thought was great only to come back to it weeks later and realize it wasn’t as great as you thought it was? When you first create something, you are highly invested in it and have what is known as a subjective point of view. But time, being our friend, allows us some distance, the pain of creating is forgotten, and then we can see our product with a clear, objective view.

3. Pressure is Good

This third axiom is about deadlines. James set for himself a self-imposed deadline of three years for his product. He knew that without a deadline, nothing is usually done. I asked my classes what would happen if I gave them a project to do for the class without putting any deadline on it. They all agreed I would never see them. When I was a new college teacher fresh out of grad school, I realized that if I didn’t impose deadlines on myself to create artwork while I was teaching, there would be a strong possibility I would become one of those teachers that taught art but no longer did it myself. So my solution was to enter street art fairs during the summer months to sell my work, and this meant I had to produce. So for the next 45 years, I entered 6-9 street art fairs each summer all over the midwest. I never regretted that decision. It made me a better artist and a better teacher.

This ends part one of a two-part series. On my next post, I will explore the concept of divergent and convergent thinking in greater depth. Because creativity is a verb and not a noun, we can all become more creative. It is simply something that we do; it is not something that we are. If we have nibbled ourselves away from the creative process, we can also nibble our way back to it. Hopefully, these posts will give some of my readers courage to find their way back to the creative spirit that God gave us as our birthright. Also in future posts, I will talk about the creative mindset and the creative attitudes that we must develop on our journey back to our God-given creativity so that we may more accurately reflect Him.

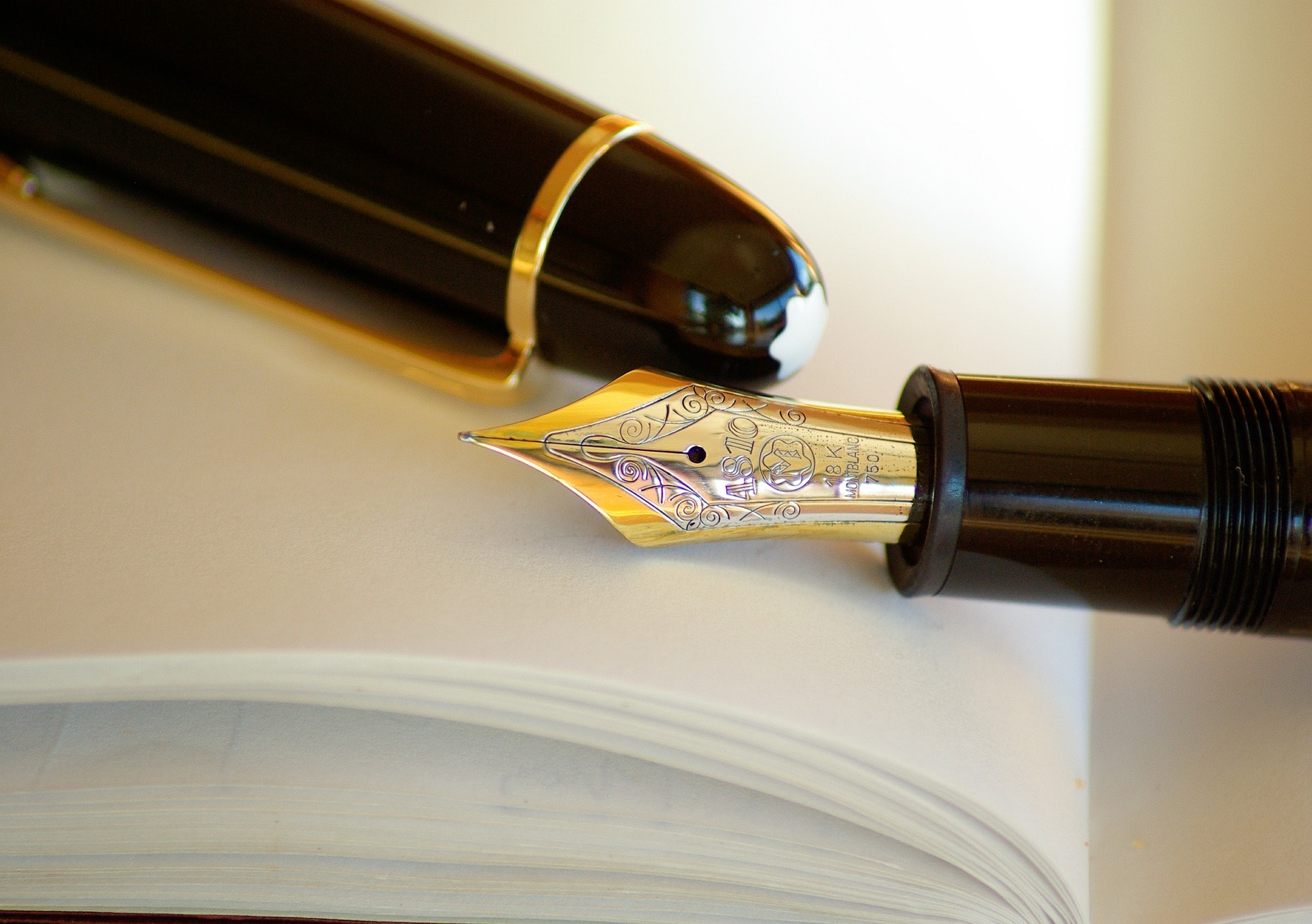

Featured Image by Gary Wilson

This post was written by Gary Wilson, who has been working as a professional artist since 1969. After receiving his B.F.A. from Bethel College in St. Paul, Minnesota, and an M.F.A. from Michigan State University, Mr. Wilson taught as an Associate Professor of Art at Monroe Community College from 1971 until 2016, where his course load included Ceramics, Drawing, Art History, Art Appreciation and Creativity.

Having developed a college course in creativity which he has taught for over 40 years, he is able to communicate to others how to take the mystery out of the creative process. To learn more about Gary’s art and mission, or to read more of his Collective posts, head on over to his member page here.

A Christian View of Design

A Christian View of Design  Breakthrough: Enneagram Coaching With Sue Mohr

Breakthrough: Enneagram Coaching With Sue Mohr  The Tension Between Creatives and the Church

The Tension Between Creatives and the Church